Check us out today. And let us hear from you. We're always ready to help.

Copyright 2011 AmSAW

Sharing

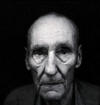

a birth date with another of the world's most popular literary figures,

Fyodor Dostoevsky, is an American pop icon, Kurt

Vonnegut Jr. Born in Indianapolis, Indiana, on November 11, 1922,

Vonnegut was the youngest of the

three children of Edith and Kurt Vonnegut. He is the author of numerous novels,

including Cat's Cradle (1963), Hocus Pocus (1990), and Timequake (1997).

Sharing

a birth date with another of the world's most popular literary figures,

Fyodor Dostoevsky, is an American pop icon, Kurt

Vonnegut Jr. Born in Indianapolis, Indiana, on November 11, 1922,

Vonnegut was the youngest of the

three children of Edith and Kurt Vonnegut. He is the author of numerous novels,

including Cat's Cradle (1963), Hocus Pocus (1990), and Timequake (1997).  In December 1944, Vonnegut was captured by the Germans at the Battle

of the Bulge. He was imprisoned in a slaughterhouse in Dresden, Germany,

and forced to work in a factory that manufactured food supplements for

pregnant women. Allied bombers attacked the city on the night of

February 13,

1945,

setting off a firestorm that burned up the oxygen and killed nearly all of

the city’s residents within hours. Vonnegut and his fellow prisoners

survived because they slept in a meat locker three stories belowground.

When they went outside the following morning, they found themselves among

few people left alive in a city that had burned to the ground.

In December 1944, Vonnegut was captured by the Germans at the Battle

of the Bulge. He was imprisoned in a slaughterhouse in Dresden, Germany,

and forced to work in a factory that manufactured food supplements for

pregnant women. Allied bombers attacked the city on the night of

February 13,

1945,

setting off a firestorm that burned up the oxygen and killed nearly all of

the city’s residents within hours. Vonnegut and his fellow prisoners

survived because they slept in a meat locker three stories belowground.

When they went outside the following morning, they found themselves among

few people left alive in a city that had burned to the ground. It’s easy to

understand the sci-fi label. Vonnegut’s first published novel, Player Piano,

depicts a fictional city called Ilium in which the people have surrendered

all control of their lives to a computer named, ironically enough, EPICAC,

after a substance that induces vomiting. The Sirens of Titan (1959)

takes place on several different planets, including a thoroughly militarized

Mars, where the inhabitants are controlled electronically.

It’s easy to

understand the sci-fi label. Vonnegut’s first published novel, Player Piano,

depicts a fictional city called Ilium in which the people have surrendered

all control of their lives to a computer named, ironically enough, EPICAC,

after a substance that induces vomiting. The Sirens of Titan (1959)

takes place on several different planets, including a thoroughly militarized

Mars, where the inhabitants are controlled electronically.  In God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater; or, Pearls before Swine

(1965), Vonnegut introduces one of his most endearing characters in Eliot

Rosewater, a philanthropic but ineffectual man who tries to use an inherited

fortune for the good of humanity. He soon learns, though, that his

generosity, his concern for humanity, and his attempts to reach out to his

fellow human beings are looked at as madness by a money-conscious society.

The novel takes pot shots at everyone, including organized religion,

suggesting that the keepers of the faiths use religious doctrine to justify

and maintain their power over others.

In God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater; or, Pearls before Swine

(1965), Vonnegut introduces one of his most endearing characters in Eliot

Rosewater, a philanthropic but ineffectual man who tries to use an inherited

fortune for the good of humanity. He soon learns, though, that his

generosity, his concern for humanity, and his attempts to reach out to his

fellow human beings are looked at as madness by a money-conscious society.

The novel takes pot shots at everyone, including organized religion,

suggesting that the keepers of the faiths use religious doctrine to justify

and maintain their power over others. Slaughterhouse-Five

was published at the height of the War in Vietnam, and antiwar protestors

saw the author as a hero and a powerful spokesperson. Vonnegut called the

work an anti-war book, although he downplayed its influence on society,

saying, "Anti-war books are as likely to stop war as anti-glacier books are

to stop glaciers." He has since become one of the most popular guest

lecturers at universities across the country.

Slaughterhouse-Five

was published at the height of the War in Vietnam, and antiwar protestors

saw the author as a hero and a powerful spokesperson. Vonnegut called the

work an anti-war book, although he downplayed its influence on society,

saying, "Anti-war books are as likely to stop war as anti-glacier books are

to stop glaciers." He has since become one of the most popular guest

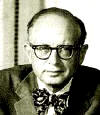

lecturers at universities across the country. It's not often that a member of academia breaks out of his field to become a best-selling author, but it happened just that way for Daniel J. Boorstin. He was born in Atlanta, Georgia, on October 1, 1914. Raised in Oklahoma, he was graduated with honors from Harvard, studied at Balliol College, Oxford, as a Rhodes Scholar, and earned his PhD at Yale.

It's not often that a member of academia breaks out of his field to become a best-selling author, but it happened just that way for Daniel J. Boorstin. He was born in Atlanta, Georgia, on October 1, 1914. Raised in Oklahoma, he was graduated with honors from Harvard, studied at Balliol College, Oxford, as a Rhodes Scholar, and earned his PhD at Yale. Boorstin's books have been translated into over twenty languages and have won numerous awards. The Americans: The Colonial Experience, the first in a trilogy of books, won the Bancroft Prize. His follow-up, The Americans: The Democratic Experience, won the Pulitzer Prize; and his third, The Americans: The National Experience, won the Francis Parkman Prize. Boorstin is one of only a few people to have won all three awards.

Boorstin's books have been translated into over twenty languages and have won numerous awards. The Americans: The Colonial Experience, the first in a trilogy of books, won the Bancroft Prize. His follow-up, The Americans: The Democratic Experience, won the Pulitzer Prize; and his third, The Americans: The National Experience, won the Francis Parkman Prize. Boorstin is one of only a few people to have won all three awards. The author's other works include The Creators, The Discoverers, and Cleopatra's Nose: Essays on the Unexpected. Boorstin has won Phi Beta Kappa's Distinguished Service to the Humanities Award and the National Book Award for Distinguished Contributions to American Letters. Daniel Joseph Boorstin died of pneumonia on Feb. 28, 2004.

The author's other works include The Creators, The Discoverers, and Cleopatra's Nose: Essays on the Unexpected. Boorstin has won Phi Beta Kappa's Distinguished Service to the Humanities Award and the National Book Award for Distinguished Contributions to American Letters. Daniel Joseph Boorstin died of pneumonia on Feb. 28, 2004.

One of the most influential authors of the Beat Generation was born on Feb. 5, 1914, in St. Louis, MO. Besides being the grandson of the wealthy inventor of the mechanical adding machine, William Seward Burroughs was one of the founders of the Beat movement that included Neal Cassidy, Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and others. Burroughs is best known for his realistic novels about drug addiction and drug culture, including Junky (1951) and Naked Lunch (1959).

One of the most influential authors of the Beat Generation was born on Feb. 5, 1914, in St. Louis, MO. Besides being the grandson of the wealthy inventor of the mechanical adding machine, William Seward Burroughs was one of the founders of the Beat movement that included Neal Cassidy, Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and others. Burroughs is best known for his realistic novels about drug addiction and drug culture, including Junky (1951) and Naked Lunch (1959). Older than the others in the group, Burroughs took on the role of father figure and mentor, encouraging Kerouac and Ginsberg in their attempts to write fiction and poetry. He felt a special affinity toward them because they were kindred spirits, dreamers, fantasizers. He said, "There couldn't be a society of people who didn't dream. They'd be dead in two weeks."

Older than the others in the group, Burroughs took on the role of father figure and mentor, encouraging Kerouac and Ginsberg in their attempts to write fiction and poetry. He felt a special affinity toward them because they were kindred spirits, dreamers, fantasizers. He said, "There couldn't be a society of people who didn't dream. They'd be dead in two weeks." On September 6, 1951, Burroughs accidentally killed his wife at a party while attempting to shoot a martini off her head with a pistol. He was stoned, and the bullet penetrated her forehead, killing her instantly. He was taken into custody and charged in Mexico City with criminal imprudence. His parents took over the care of William Junior and brought him to their home in Florida.

On September 6, 1951, Burroughs accidentally killed his wife at a party while attempting to shoot a martini off her head with a pistol. He was stoned, and the bullet penetrated her forehead, killing her instantly. He was taken into custody and charged in Mexico City with criminal imprudence. His parents took over the care of William Junior and brought him to their home in Florida.  Burroughs continued to work on the book until its publication in 1959, thinking of it as a picaresque novel narrated by his alter ego, "William Lee." His biographer, Ted Morgan, understood that Burroughs shared the "New Vision" of the writer as an outlaw, creating a "literature of risk." The compression and urgency of Naked Lunch in "the fragmentation of the text is like the discontinuity of the addict's life between fixes....For Burroughs sees addiction as a general condition not limited to drugs. Politics, religion, the family, love, are all forms of addiction. In the post-Bomb society, all the mainstays of the social order have lost their meaning, and bankrupt nation-states are run by 'control addicts.'"

Burroughs continued to work on the book until its publication in 1959, thinking of it as a picaresque novel narrated by his alter ego, "William Lee." His biographer, Ted Morgan, understood that Burroughs shared the "New Vision" of the writer as an outlaw, creating a "literature of risk." The compression and urgency of Naked Lunch in "the fragmentation of the text is like the discontinuity of the addict's life between fixes....For Burroughs sees addiction as a general condition not limited to drugs. Politics, religion, the family, love, are all forms of addiction. In the post-Bomb society, all the mainstays of the social order have lost their meaning, and bankrupt nation-states are run by 'control addicts.'"  Burroughs published several more novels, including Queer, which he wrote in 1951 but wasn't able to get published until 1985. The book shared the same protagonist as Junky, but the homosexual subject matter--although handled honestly--was considered in poor taste and kept the book from being published at the time.

Burroughs published several more novels, including Queer, which he wrote in 1951 but wasn't able to get published until 1985. The book shared the same protagonist as Junky, but the homosexual subject matter--although handled honestly--was considered in poor taste and kept the book from being published at the time.